With a combined application of empirical evidence, academic research and opinion, this essay will assess the impact that the popular printed press had on policy and communication, focusing on not only the surprise outcome of the 1992 election, but also the ultimately successful electoral strategy of the Labour Party from 1992 to 1997. It will also explore elements of historical comparison and contrast.

Both the political landscape and the printed media coverage for the 1964 election campaign and its 1992 counterpart are remarkably similar; the outcomes, however, reveal a stark contrast. It is this fascinating juxtaposition between the two respective results which provides the spark for this exploration, including how it potentially hardened the future Labour leadership’s resolve to court a previously hostile media organ, in glaring contrast to the previous incumbent’s ambivalence. The 1997 campaign’s success was achieved in no small part through political courtship (and subsequent mutual support) of Rupert Murdoch, following Blair’s ascension to the leadership of the Labour Party in the aftermath of John Smith’s untimely passing in 1994. Blair was also assisted by the implosion of the Conservative party under John Major’s leadership between 1992/97. By the time the 1997 election took place, the Conservatives had been in power for eighteen years. A combination of recurring scandals and a recognisably charismatic opponent in Blair made their position increasingly precarious. This combination of events will be investigated and thus, the essay will also assess the need of the Labour Party to acquire the endorsement The Sun newspaper in 1997 and pose the following question: Was The Sun as influential as it claimed to be or were they simply swimming with the popular tide, as some academics, political commentators and experienced journalists believe?

With a Conservative Party overall majority of twenty one and, contrary to the findings of the vast majority of opinion polls, the outcome of the 1992 UK General Election defied the predictions and expectations of all the recognised polling data gatherers. Whilst this may be nothing new in the constantly shifting political sands of 2017, it was a shock across all strata of political discourse at the time. Butler and Kavanagh claim that “the 1992 election in Britain will be long remembered, like the 1948 presidential election in the United States of America, for the opinion poll’s disastrous error in predicting the results” (Butler and Kavanagh, 1992: 135). The consensus of the polls was thus that it was broadly felt that the very best that John Major’s ruling Conservative party could hope for was a hung parliament and Major forming a coalition with minority parties. While most polls predicted a very narrow Labour victory, the incumbent Energy Secretary, John Wakeham, felt “we were always sure we would continue to be in government after the election, but possibly in more difficult circumstances” (Crewe & Gosschalk, 1995: 6).

While Wakeham radiated confidence amongst his Conservative cohort, Labour, led by Neil Kinnock, exuded a similar unswerving self-belief. This was most prominently displayed during his now infamous American influenced address at a Labour election rally at the Sheffield Arena, a week before the polls opened. It is of singular importance to recall that during the 1987 election campaign Kinnock had been mercilessly vilified by The Sun and this hostility continued, both throughout the parliamentary term and in the 1992 election campaign. In a possible retaliatory move and with a policy declaration that Freedman claims was “clearly aimed at Murdoch” (Freedman, 2003: 158), “the 1992 Labour manifesto committed a future Labour government to establish an urgent inquiry by the Monopolies and Mergers Commission into the concentration of media ownership.” (Griffiths and Heppell, 2012: 148.) It would be fair to assume that Kinnock either did not think Murdoch or his most popular media organs, had sufficient influence over the electorate, or he was being courageous to the point of irresponsibility with this policy pledge. Even allowing for the second possibility, Kinnock must still have believed that he could win the 1992 election without the support of The Sun. “Kinnock will have been aware of the similar campaigns of press vilification against Harold Wilson in 1964” (Franklin, 1994: 152) and Kinnock would have been in a near identical position to Wilson too. Kinnock was contesting an election against a Tory party who had been in government for thirteen years and with the introduction of the Community Charge two years prior, recently had a turbulent period of controversy, combined with a fractious change of leader soon after. In 1964, Wilson contested an election against a Conservative Party who had been in power for fourteen years and with the recent Profumo scandal and subsequent resignation of Harold Macmillan, had also been embroiled in a tempestuous period. The crucial difference was that despite all the press hostility in October 1964, Wilson won the election against Sir Alec Douglas Home, Kinnock lost against Major in April 1992.

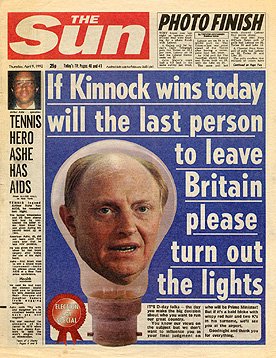

On the day of the 1992 election, The Sun led its front page with what is now regarded as one of its most famous ever headlines. “If Kinnock wins today will the last person to leave Britain please turn out the lights” (Thomas, 2005: 87). In 1992, The Sun‘s daily circulation was calculated as 3,588,077 (Griffiths & Ison, 2001: 89), which comfortably made it the highest selling newspaper in the UK. With these figures and with their grammatically dubious boast two days after the election of “It Was The Sun Wot Won It” (Lange, 1999: 11) and combined with the widespread public expectancy of Neil Kinnock succeeding John Major, senior figures in the Labour Party eventually decided to appease The Sun and its proprietor once Kinnock’s successor, John Smith, suddenly passed away in May 1994.

Prior to the 1992 election campaign commencing in earnest, Kinnock said “elections are not won in the three weeks of campaign, they are won in two years of hard work and preparation” (Heffernan & Marqusee, 1992: 301). Guardian columnist and future Labour MP, Martin Linton contradicted Kinnock.

“Linton’s analysis estimated that there was a swing during the three months before the election of 8% to the Conservatives from Sun and Daily Star readers, but no swing at all from Daily Mirror readers” (Thomas, 2005: 98)

If Kinnock sincerely believed that pre-election statement and did not initially believe that Murdoch’s media organs were of crucial influence, he subsequently expressed a volte face five days after the election. Kinnock said during his party leadership resignation speech, that the media had “enabled the Tory party to win again, when it could not have secured victory on the basis of its own record, its programme or its character” (Thomas, 2007: 1).

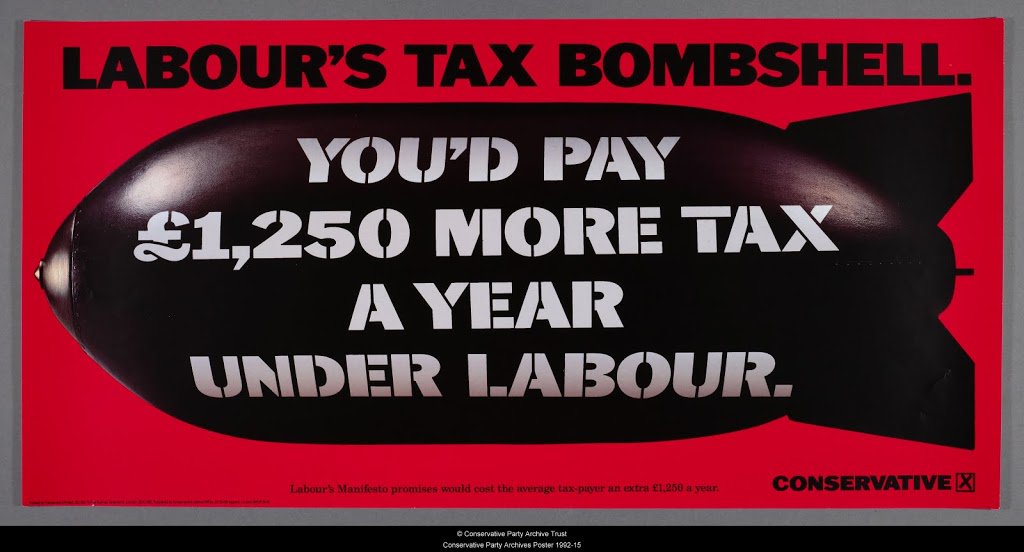

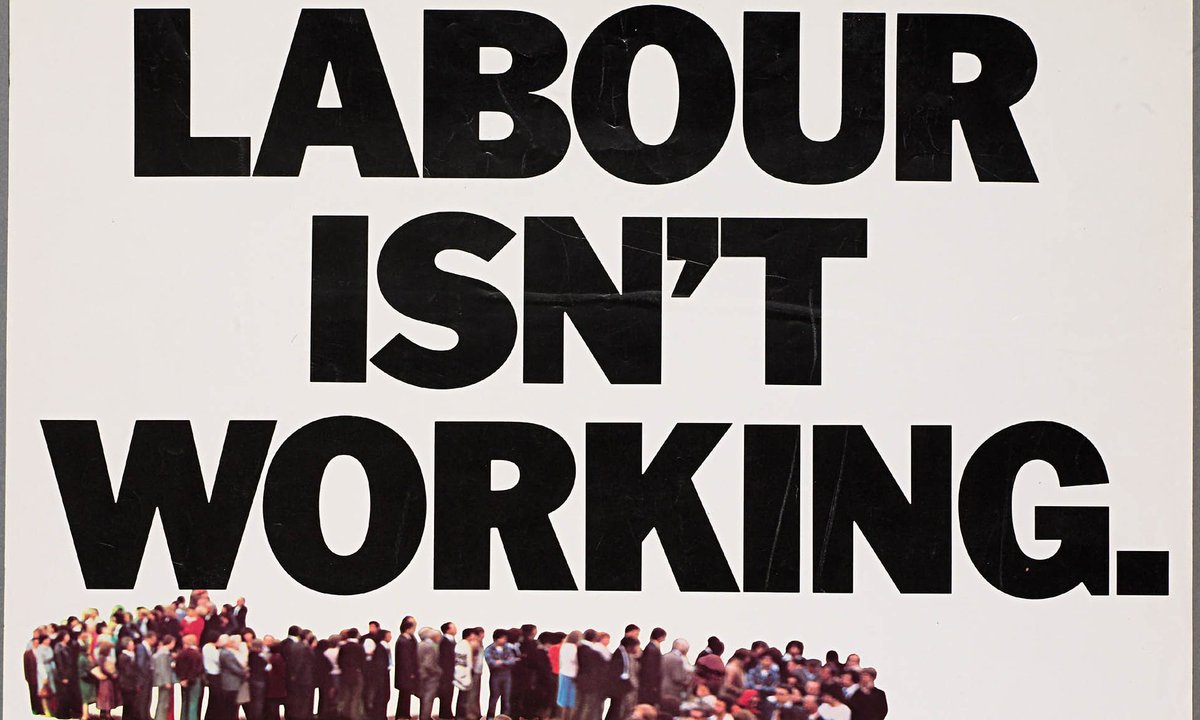

Linton’s statistics and The Sun’s triumphalist front page soon after the election may have strongly influenced Kinnock’s emotional rhetoric in his resignation speech. While Kinnock and Linton cite the media’s influence, there is evidence that the Tory campaign and their public relations strategists, Saatchi & Saatchi, were having a strong impact on voter’s intentions. The memorable slogan, “Labour’s Tax Bombshell’, ‘Five Years Hard Labour’ and Labour’s private polling showed that this did register with voters” (Butler & Kavanagh, 1992: 252) were just as powerful as their now iconic slogan of ‘Labour Isn’t Working’ in 1979. This would strengthen the theory that publicists can have at least as strong an impact on party political media policy as mainstream media outlets themselves. While the Conservatives had since 1979, used Saatchi and Saatchi to great success, Tony Blair sought the experience of Alastair Campbell, a time served political journalist and an appointment which proved equally successful.

With Kinnock’s resignation speech embedding itself into the psyche of the Labour Party and with The Sun’s “relentless and vicious campaign of Labour leaders and their policies” (McNair, 2011: 55), Tony Blair decided upon winning the Labour leadership election in July 1994, to “work assiduously to break down the antagonism of the Murdoch press to the Labour party” (McKie, 1998: 117). The Sun had been fiercely pro Conservative since they switched the organ’s affiliation from Labour to the Tories, for the Ilford by-election in March 1978. However, during a visit to Australia in July 1995, Blair’s strategy saw a significant breakthrough in acquiring the support of The Sun. In Australia, incumbent Labor Prime Minister, Paul Keating, advised Blair on exactly how to gain Murdoch’s approval. In his diaries, Blair’s press secretary, Alastair Campbell, said that Blair was told by Keating that “You can do deals with Murdoch, without ever saying a deal is done. But the only thing he cares about is his business and the only language he respects is strength” (Campbell & Stott, 2007: 71). That visit to Australia also saw Blair deliver a speech to “a conference of News International managers which was intended as a courtship display to attract Murdoch’s support” (Simpson, 2010: 522). During that speech, Blair said that “the new right get certain things right, a greater emphasis on enterprise and rewarding, not penalising success” (Abel, 2003: 16/17). It would be difficult to imagine Kinnock courting senior personnel in Murdoch’s employ or making concessions about how correct ‘the new right’ were in their stated beliefs. Corfe describes Blair’s “mentality of being so pragmatic as to be value free” (Corfe, 2008: 90) and Blair’s determination and “willingness to court the Murdoch empire” (Goes, 2016: 57) would give credence to Corfe’s assertion.

In contrast to Kinnock’s pledge of party policy at the previous election of an enquiry into media concentration (Griffiths & Heppell, 2012: 148 & Freedman, 2003: 158), Blair “made it clear in his speech to News International executives that he wanted an open and competitive media market” (O’Malley & Soley, 2000: 94). This policy declaration that Blair made is a classic example of Keating’s previously alluded to assertion to Blair about making deals without explicitly saying it is done (Campbell & Stott, 2007: 71). Blair could also truthfully “deny that any private deal was stuck” (Heffernan, 2001: 207) by saying that a competitive media market was what he wanted in the speech. It was not a stated promise. However, Blair knew that was what Murdoch wanted to happen and with John Major having recently fought a leadership election to save his political career, Blair’s timing to appease Murdoch was perfect to exploit his increasingly vulnerable opponent at 10 Downing Street.

Whilst Blair was making significant progress in his attempts to gain Murdoch’s approval, Butler and Kavanagh argue that due to the increasing unpopularity of the incumbent Conservative government, the respective scandals and the contemporary colloquial identification with ‘sleaze’, the Labour Party did not need the support of The Sun. “Labour made a breakthrough in its methods of campaigning before and during the election. But the differences between the parties in using these skills and techniques did not decide the election” (Butler & Kavanagh, 1997: 252). With these methods of campaigning and a leader in Blair, who was widely perceived as young and vibrant, Labour were in a prime position to capitalise on what had been an extremely unstable parliamentary term for the Conservative Party. Four months after the previous election, Chancellor of the Exchequer, Norman Lamont, had to deal with what is colloquially known Black Wednesday, where “Britain was forced out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism and the value of Sterling fell dramatically in the months that followed” (McNaughton, 2003: 21). In June 1995, due to rising tensions in the Conservative Party, John Major resigned as leader of the party, to force what was effectively a mandate of confidence in his premiership. Major prevailed in this election against John Redwood, but his campaign coincided with Blair’s successful pitch to News International executives. The Conservatives were also deeply damaged by the ‘cash for questions’ affair, which involved an allegation made by The Guardian in October 1994 about the conduct of Conservative MP for Tatton, Neil Hamilton. When Hamilton subsequently withdrew his libel action against The Guardian on the eve of the court hearing two years later, he and by extension, the Conservative Party were perilously damaged. The 1997 election saw Hamilton lose his parliamentary seat, to former Broadcast Journalist and Independent candidate, Martin Bell. Tatton, a seat widely considered to be a safe Conservative constituency and with a Tory majority of 15,860 in 1992, is an indicator of the malaise which had affected the entire Conservative Party during this parliamentary term. Toye and Gottlieb claim that “since 1992, The Sun’s former bedfellows became unelectable. Instead of jumping ship, The Sun was being forced to walk the Tory plank straight into the open arms of new Labour” (Toye & Gottlieb, 2005: 187). Woodrow Wyatt, an experienced journalist and former employee of Murdoch’s said “Rupert has behaved like a swine and a pig, he doesn’t like backing losers and he thinks Major will lose” (Brighton & Foy, 2007: 80). Wyatt, who was also a former Labour MP, did not think that Blair needed Murdoch’s support.

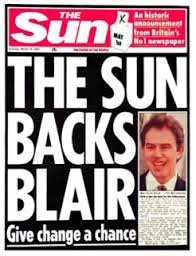

These efforts were proved to be fruitful when on the 18th March, 1997, with a front page lead, “The Sun unequivocally switched its editorial line behind Tony Blair” (Conboy, 2007: 78). Fergus Shanahan, contemporary Night Editor for The Sun said “It did not take much insight to realise the Tories were making themselves unbackable and it was clear by early 1997 that the country had had enough and wanted a change” (Toye & Gottlieb, 2005: 187). Whilst this was obviously a signal of a very successful campaign to win the editorial approval of The Sun, Reeves, Mckee and Stuckler “estimate that The Sun‘s decision to switch parties generated about 525,000 votes for the Labour party in 1997” (Reeves, Mckee and Stuckler, 2015: 3) and Labour garnered “two million more votes than in the previous general election of 1992” (Whitely & Seay, 2003: 301). If that estimation is accurate, then Labour would have won the 1997 election without The Sun‘s support. However, Tony Blair was effusive in his gratitude Stuart Higgins, saying in a letter to the Sun editor “thanking him for the paper’s ‘magnificent’ support which really made the difference” (Butler & Kavanagh, 1997: 183)

Basildon, in Essex, is a strong case in favour of seeking The Sun’s editorial influence and approval. People “interviewed in Basildon identified themselves overwhelmingly as working class” (Storrar & Morton, 2004: 389). This makes Basildon the type of seat that is essential that Labour win, if they were to form a government. In 1997, “Labour won Basildon by 13,280 votes” (Waller & Criddle, 2007: 128), However, in 1992, the Conservatives held the Basildon constituency with a majority of 1,480. “Basildon has the highest proportion of Sun readers in the country” (Watts, 1997: 41) and with the necessity to win constituencies like this, Labour media strategists believed that The Sun’s support would be advantageous in winning these parliamentary seats. However, this belief was not unanimous. “Ivor Crewe has calculated that the impact of the Sun’s campaigning was worth no more than six highly marginal seats” (Barnett & Gaber, 2001: 26). Crewe’s calculation may very well be correct, however, the scale of the swing from Conservative to Labour between 1992 to 97 was indicative of the disillusion that voters with the Conservative Party. Basildon was not a seat that Labour won from the Tories with a slim margin. With over a 13,000 majority, they won the seat emphatically from a party that had held it for eighteen years. This Labour win, combined with its famous gain of Enfield, the seat of Defence Secretary, Michael Portillo, along with the Tories losing Tatton could also be an indicator that the Conservatives would have lost the election even if The Sun had backed them.

Whilst Griffiths and Ison claimed that The Sun’s circulation was 3,588,077 in 1992, Professor Roy Greenslade claimed in March 1997 that The Sun “has a daily readership of more than 10 million” (Greenslade, 1997). Whilst there is obviously a significant difference in the circulation calculation, both commentators are agreed that The Sun was a heavily consumed distributor of information. While broadly speaking, these figures would discredit the perceived influence that The Sun had on its audience. Despite John Wakeham’s assertions of quiet confidence amongst his Conservative colleagues during the 1992 campaign and such was the partisan savagery of The Sun’s coverage of the Labour Party campaign and their triumphant headline the day after the Conservatives won the election, the Labour Party were taking no chances of such hostile coverage again from the highest selling newspaper in the country.

In summary, the fact that Neil Kinnock made no attempt to appease Rupert Murdoch’s media interests, indeed, quite the contrary, gives clear indication that he did not think their support was of sufficient importance to win the election in 1992. Harold Wilson’s election victory in 1964 and the media hostility that he encountered en route to becoming Prime Minister will have been an inspiration to Kinnock. Despite The Sun’s significant audience and strong conviction in expressing their ideology, Reeves, et al (2015: 8) and Toye & Gottlieb (2005: 187) would appear to concur with Kinnock’s belief. For the 1997 campaign, McNair says, “The British people had grown tired of the Tories and sceptical of their messages.” (McNair, 2011: 106.) Along with Butler and Kavanagh’s (1997: 252) assertion of Labour’s campaigning methods and with the Conservatives being in power for eighteen years, there is strong substance to the claim that Tony Blair and, by extension the Labour Party, did not need the support of The Sun. This would also give credence to the belief that Kinnock’s claim in his leadership resignation speech (Thomas, 2007: 1), was more of an emotional reaction of a man who had just unexpectedly lost, than that of any scientific evidence or conviction. The Sun’s typically hyperbolic headline (Lange, 1999: 11), coming a mere two days after Major’s re-election, may have subconsciously influenced Kinnock into making that claim three days hence.

While Labour won the seat of Basildon and with its high proportion of Sun readers acknowledged, the emphasis of Labour’s election victory in both votes cast and seats won, a victory which even surpassed Margaret Thatcher’s 1983 landslide, would strongly back up Woodrow Wyatt’s belief about Blair’s requirement of Murdoch’s support. Whether the support of The Sun was decisive or not for the outcome of the 1992 election, there is little doubt that it had a momentous influence on how Labour nurtured its relationship with Murdoch’s media interest for the election in 1997. Blair’s letter of gratitude to the editor of The Sun immediately after his party’s win is emphatic in expressing how important his paper’s support was (Butler & Kavanagh, 1997: 183). When Blair prevailed over John Prescott for the party leadership in 1994, he and the Labour party’s main media strategists decided that winning the support of The Sun for the party’s leader, if not the party itself, was crucial for its chances of victory in the 1997 election.

Once in power, Blair would continue to be of help to Murdoch. “In March 1998, on behalf of Murdoch, Blair contacted his Italian counterpart, Romano Prodi and asked whether his government would block Murdoch’s proposed bid for Silvio Berlusconi’s television network” (Curran & Seaton, 2010: 57). Tony Blair’s speech to News International management in 1995 and, in particular, his pledge to rescind the previous stated party policy of an inquiry into the concentration of media ownership” (Griffiths & Heppell, 2012: 148), was a seismic change in media policy from Kinnock’s period as party leader. It was a change of policy that was shaped by the perceived power of Murdoch’s most popular media organ and its influence on its readership and it was ultimately a success, even if there is plenty of dispute about its necessity.

Bibliography

Abel, Richard L; English Lawyers Between Market and State: The Politics of Professionalism (2003) Oxford: Oxford University Press

Barnett, Steven & Gaber, Ivor; Westminster Tales: Twenty-first-Century Crisis in Political Journalism, The (2001) London: Continuum

Beetham, David Democracy Under Blair: A Democratic Audit of the United Kingdom (2002) Indiana: Indiana University

Brighton, Paul & Foy, Dennis; News Values (2007) London: Sage

Butler, David & Kavanagh, Dennis Basingstoke; British General Election Of 1992, The (1992) Macmillan Press, The

Butler, David & Kavanagh, Dennis Basingstoke; British General Election Of 1997, The (1997) Macmillan Press, The

Campbell, Alastair & Stott, Richard; Blair Years, The: Extracts From The Alastair Campbell Diaries (2007) London: Arrow Books

Conboy, Martin; Language Of The News, The (2007) Oxon: Routledge

Corfe, Robert; Social Capitalism In Theory And Practice: Emergence Of The new Majority (2008) Bury St Edmonds: Arena

Crewe, Ivor & Gosschalk, Brian; Political Communications: General Election Campaign Of 1992. The (1995) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Curran, James & Seaton, Jean; Power Without Responsibility (2010)

Franklin, Bob; Packaging Politics: Political Communications In Britain’s Media Democracy (1994) London: Hodder Headline Group

Freedman, Des Television Policies Of The Labour Party 1951-2001 (2003) London: Frank Cass Publishers

Greenslade, Roy; It’s the Sun wot’s switched sides to back Blair (1997)

https://www.theguardian.com/politics/1997/mar/18/past.roygreenslade (Retrieved 10:41 hours; December 22nd 2016)

Greenslade, Roy; Press Gang: How Newspapers Make Profits From Propaganda (2004) London: Pan MacMillan

Goes, Eunice; Labour Party Under Ed Milliband, The (2016) Manchester: Manchester University Press

Griffiths, Simon & Heppell, Timothy; Leaders of the Opposition: From Churchill to Cameron (2012) Hampshire: Palgrave MacMillan

Griffiths, Alan & Ison, Stephen; Studies In Economics and Business (2001) Oxford: Heinemannn Educational Publishers

Heffernan, Richard New Labour And Thatcherism: Political Change in Britain (2001) London: Palgrave Macmillan

Heffernan, Richard & Marqusee, Mike; Defeat from the Jaws of Victory: Inside Kinnock’s Labour Party (1992) London: Verso

Kelley. Stanley; Law And Contemporary Problems – Volume 27 (1962) Durham, North Carolina: Dukes University

Lange, Yasha; Media And Elections: Handbook (1999) Strasbourg: Council of Europe

Mckie, David; Bartle, John; Crewe, Ivor & Gosschalk, Brian; Political Communications: Why Labour Won the General Election of 1997 (1998) Oxon: Routledge

McNair, Brian; Introduction To Political Communication, An, [Fifth Edition] (2011) Oxon: Routledge

McNaughton, Neil; Understanding British And European Political Issues (2003) Manchester: Manchester University Press

O’Malley, Tom & Soley, Clive; Regulating The Press (2000) London: Pluto Books

Reeves, Aaron; Mckee, Martin & Stuckler, David; It’s The Sun Wot Won It’: Evidence of media influence on political attitudes and voting from a UK quasi-natural experiment (2015) http://users.ox.ac.uk/~chri3110/Details/Sun%20paper.pdf (Retrieved 10:31 hours; December 20th 2016)

Simpson, John; Unreliable Sources: How The 20th Century Was Reported (2010) London: Pan Macmillan

Storrar, William & Morton, Andrew; Public Theology for the 21st Century: Essays in Honour of Duncan B. Forrester (2004) London: T & T Clark Ltd

Thomas, James; Popular Newspapers, Labour Party And British Politics, The (2005) Oxon: Routledge

Thomas, James; Popular Newspapers, Labour Party And British Politics, The (2007) Oxon: Routledge

Toye, Richard & Gottlieb, Julie; Making Reputations: Power, Persuasion and the Individual in Modern British Politics (2005) London: IBTauris

Waller, Robert & Criddle, Byron; Almanac Of British Politics, The (2007) Oxon: Routledge

Watts, Duncan; Political Communication Today (1997) Manchester: Manchester University Press

Whiteley, Paul & Seyd, Patrick; How to win a landslide by really trying: the effects of local campaigning on voting in the 1997 British general election (2003) http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0261379402000173/1-s2.0-S0261379402000173-main.pdf?_tid=8c46aeea-c775-11e6-afb0-00000aab0f01&acdnat=1482322016_36fb408ea413cf3849be449de2db9ddc (Retrieved 16:07 hours; December 20th 2016)